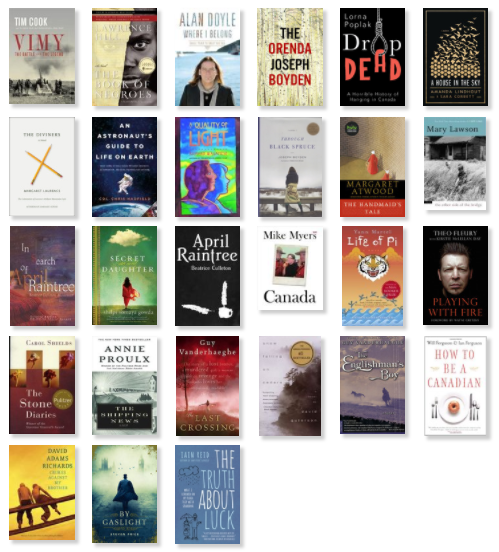

ELA A30 Critical Analysis Essay – While you Read

The second essay you’ll write for your Canadian Lit course is one that reviews the good and bad of the author’s writing in the novel you chose. While you read, it is helpful to look for examples that you could take note of and use while developing your essay.

As you read, keep a running list of what you like or don’t like about their writing, including things like:

- There is a list of characteristics to consider for Fiction reading

- And another list of characteristics specific to Non-fiction reading (true stories)

For Fiction Texts:

- their development of characters – Are they believable characters or have a well-developed background? Are the characters (especially main one) slowly developed as the story moves on or does the author clump details of a character together at once?

- the pace of the writing – do some things happen too slow or too fast? Some events that build in excitement likely should speed up in pace, but some authors develop them too slowly, which can kill the vibe of the moment.

- what about language choice? Do they use too many unfamiliar words making it challenging to follow along with the idea of the story? Does their use of bigger vocabular seem awkwardly used, like the words don’t fit smoothly? Is the language written below the reading level you expected and is dull to read because of the word selections?

- Length of chapters: Are the chapters too long to maintain an interest in what’s happening? Is there a natural and appropriate break developed between chapter events, or does that author stop chapters at times that are inconvenient for you as a reader?

- Sentence writing complexity: Are the sentences comfortable to read or just at the right level of challenge for you as a reader, or are they too simple and short? Or could they be overly wordy and long, making it challenging to understand the writing.

- Descriptive writing: Does the author do a good job of developing description in the writing, creating images for you to imagine as you read, or do they just “tell” a lot in their writing. Is the manner of their descriptive writing effective, or is it done poorly and falls below what you’d judge as “good writing”?

- The Storyline: Have they created an interesting story? One that you’re drawn into and compelled to follow along with? Have they developed in you the reader an interest in the outcome of the story?

- Supporting characters: Who else for characters has the author developed for the storyline? Are there too many characters introduced too close together so that it makes it challenging as the reader to keep people separated in your mind? Do they include too complex of a cast of characters that it’s hard to keep everyone straight, what their relationships are too each other?

- Setting: How does the author use the location and span or placement of time to help support the plot elements in the story? Do things happen over the right amount of time or are they squished into too short a time period/drawn out into too long of one? Does the location support the plot or interfere with it?

- Point of view: The author will have told the story from the perspective of a voice – was that voice in 1st, 2nd, or 3rd perspective (limited or omniscient)? Sometimes a 1st person point of view narrative can be limiting, so maybe was’nt the best choice or was challenging to accept as the reader. Did your author’s selection and development of the point of view work well or poorly in the reading, according to you?

- Rising Action/Complications: How did the author continue to develop tension throughout the book? Did they drop it in occasionally and clumsily, or was it well developed and grew in a way that drew you in as the reader?

- Climax: Did the tension leading to the climax moment in the book support that pivotal moment or did the climax happen sort of awkwardly, jumping ahead in intensity without being properly developed for the reader?

For Non-fiction Texts:

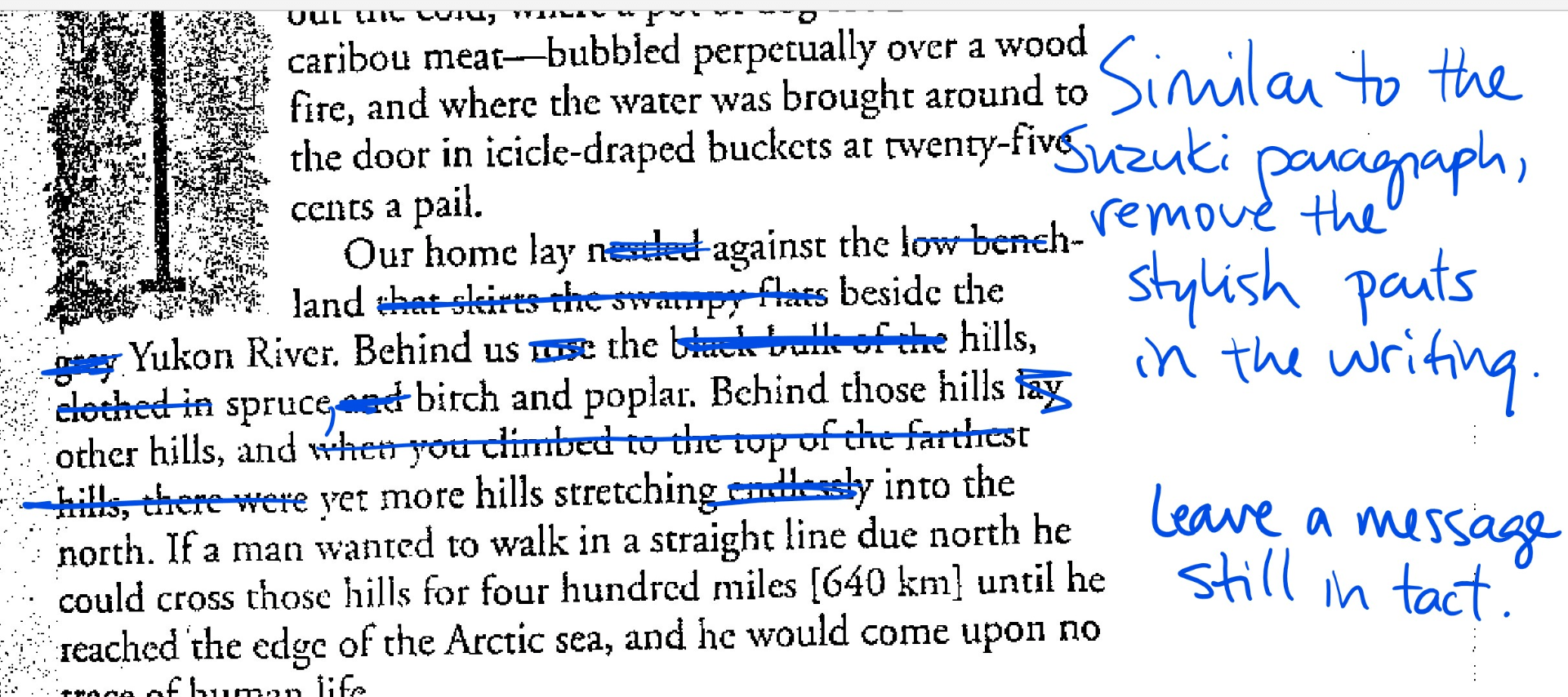

- Word choice throughout the writing: by their personal choices, do they make it interesting and engaging for a reader, regardless of the complexity of the topic?

- Inclusion of anecdotal stories (personal stories): are they developed clearly enough? Does the author tell you more than is needed or do they miss some key parts of a personal story?

- Pace of the information: Does the author write too much about something that isn’t quite interesting, making the pace seem to drag on? Or do they give equal time to all topics, when they could benefit from expanding on some topics in the non-fiction that are more interesting to the reader?

- Sentence variety and mechanics: What kinds of sentence variety do you notice in the writing? Do they stick to basic and simple sentence formations, or is it clear they play with the sentence variety, using repetition, parallelism or other techniques for personal style?

- Method and amount of referencing included: Often times, non-fiction texts will include reference to several types of other sources, to help support the subject covered, like published journals, personal interviews, news reports, or statistics. Does your author include these smoothly and use the right amount? Or does their inclusion of their references and sources slow and bog down the reading, making it uninteresting for you the reader?

- Writing suits target audience: It is often clear what target audience an author is writing to. If their subject matter is more serious, they’re likely writing to a more-adult audience. With the words they choose, the complexity of sentences and paragraph/chapter lengths developed, is it clear they’ve written to suit the reading and interest level of their target audience, or have they developed something too childish or mature to match the audience they’re likely targeting?

- Agenda or bias that may be distracting: Some non-fiction texts are written with a particular agenda on the part of the author. They may want people to become more supportive or open-minded of a topic, so they may write with the goal of convincing the reader of a perspective; this may be distracting if you’re someone who can’t believe as they do.

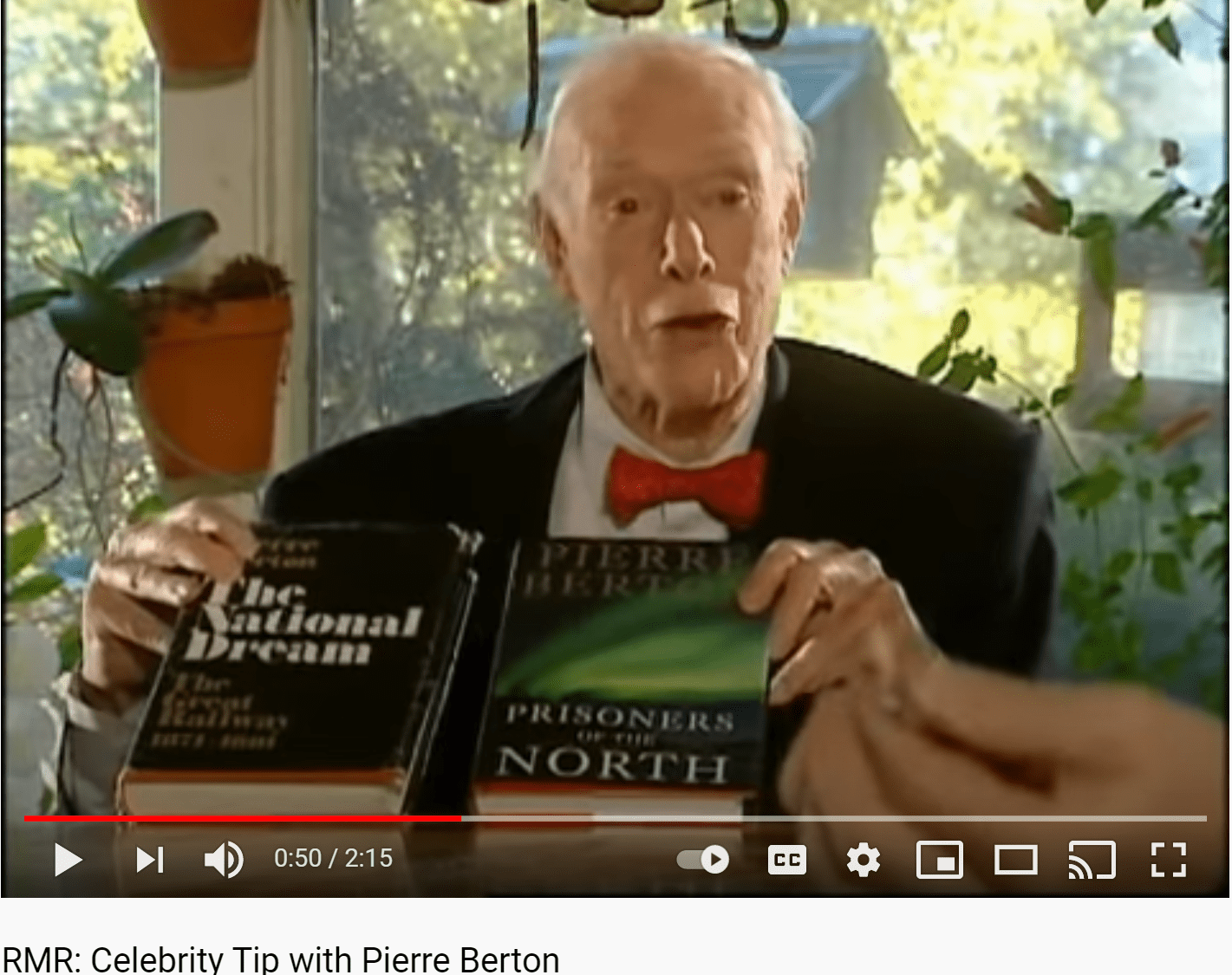

- Depth the author delves into the topic: Some non-fiction books may be written by a celebrity of someone with assumed knowledge on a topic, but their actual coverage of that topic in the writing may be quite superficial. Is the topic covered in enough detail to be interesting or is it only generally and vaguely discussed? Or you may find the opposite, that their coverage of a topic may be more academic or detailed than is appropriate for a general audience.